Wandering aimlessly through the internet, as one does, I recently discovered the bizarre world of Chinese mascot costume e-commerce websites. OK, so I wasn’t exactly wandering aimlessly, but that’s not the point. We’re going to need to stay focused in order to make it through this story, as there are a couple of junctures that will invite lengthy digression, so let’s try not to get sidetracked.

What matters, for our purposes, is that there are a bunch of very strange websites that purport to sell a dizzying variety of Chinese-made mascot costumes. The most easily-found example, shopmascot dot com, is apparently based in Jiangsu, and lists hundreds mascot costumes for sale, spanning a broad spectrum of characters and quality. Like other players in the space (joymascot, greatmascot), it follows a certain formula: a huge number of listings, a wide variety of quality, strangely small variations in pricing (almost everything is $320 or $420), and enough scam reports to make the whole genre of website seem pretty suspicious.

But before I’d even investigated the credibility of these websites (I can’t stress enough here: I really was just surfing around, and not seriously shopping for a mascot costume), something in the endless scroll of wildly diverse costumes jiggled something loose in my brain. Suddenly I realized that (as the scam reports confirm) these websites just scrape together pictures every one-off mascot costume ever ordered from China, and that there was a chance that they’d be trying (pretending?) to sell a mascot costume that I hadn’t thought of in a very long time. Sure enough, just seconds later there he was, brimming with boozy joy and on sale for just $349: Happy Lightweight Beer Cup Mascot Costume, or as we called him back in school, Sudsy motherfucking O’Sullivan.

You see, friends, this anthropomorphic mug of fermented cheer is an old college pal. As it so happens, you could even say that I bear a degree of personal responsibility for the fact that you can go out and buy a costume of him (I would try AliExpress if you must, rather than the weird mascot sites). It’s a bit of a story, but if you stick with it I think it illustrates an important point about culture in the computer age (of all things).

A long time ago, when the millennium was still new, I attended the University of Oregon as an undergraduate. Through a bizarre and slightly embarrassing chain of events I had a paper published by something called The Oregon Commentator, which is what passed for the campus right-of-center political journal at that institution. Though founded during the Reagan Revolution, the Commentator had bounced around a good deal politically over the years, and by that time had settled into a kind of “South Park libertarianism” that highlighted humor as much as opinion. Just to illustrate the extent to which “right of center” is a relative term on a campus like the University of Oregon, the first piece of mine that ever ran there argued for greater American engagement with Iran.

Within a week or so of agreeing to contribute that piece, I was hanging out at the Commentator’s office, writing jokes for filler. Then, suddenly, the editor took me aside and laid it out: everyone on staff was graduating, and I was the only candidate to take over as editor. Either I did the job, or the then nearly 20 year old magazine would go under. I said yes.

Looking back, there were a lot of potential reasons to take this bizarre first step into journalism (or something like it), but they were all overwhelmed by the avatar who represented the magazine on every cover: Sudsy O’Sullivan. Born during a late night creative session earlier in the magazine’s history, Sudsy was essentially a mug of beer with the Kool Aid Guy’s face, and the cigar-toting arms of the baby from Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Sudsy’s intellectual property-disrespecting provenance, his infectiously joyful visage, and his embodiment of the bipartisan appeal of beer sold me on the whole project. My commitment to even the squishiest forms of libertarianism was never less than extremely qualified, but under the banner of Sudsy I could gleefully troll the liberal campus bubble into new perspectives without feeling like I was part of a broader movement I didn’t actually want to be part of.

I could go on at length about the life-altering experience of running a “conservative” magazine on a liberal campus, and perhaps at some point I will, but we still have a specific story to tell here. One evening, in the midst of an all-hours push to ready an issue for publication, we realized we did not have a back cover. I don’t remember the details, probably an artist bailed on us last minute (as “conservatives,” we were lucky to get any artists to work with us!), but there we were with nothing to go on the back of the book.

Then inspiration struck. Under my editorship we’d focused the magazine’s libertarian impulses toward the student government, which actually legitimately needed someone to provide some fiscal discipline, so I filled out a “special request” form for $10,000, to be spent on a life-sized Sudsy costume, and put that on the back cover. It was intended to satirize the overuse of this budget process-evading fiscal device, but I’m not sure anyone really cared about the joke. What I had actually done is take an unwitting step towards Sudsy’s eventual transubstantiation, kicking off a process that would transform a few IP law-violating vector images and a lot of sophomoric humor into something physically real (and now available for sale online).

It’s difficult to tell the rest of the story with any real precision, because by then I had left school and moved from Eugene to Portland, but the broad strokes were relayed to me by the editor at the time. Somehow my old back cover “special request” had been found among the piles of back issues in the magazine office, and the staff were joking about how funny it would be to try to do it in real life. Then a Chinese kid on staff came back from spending the summer with family, and he had done it. It turned out his family owned a costume factory, and had created a one-of-a-kind life-sized Sudsy costume that was then donated to the publication.

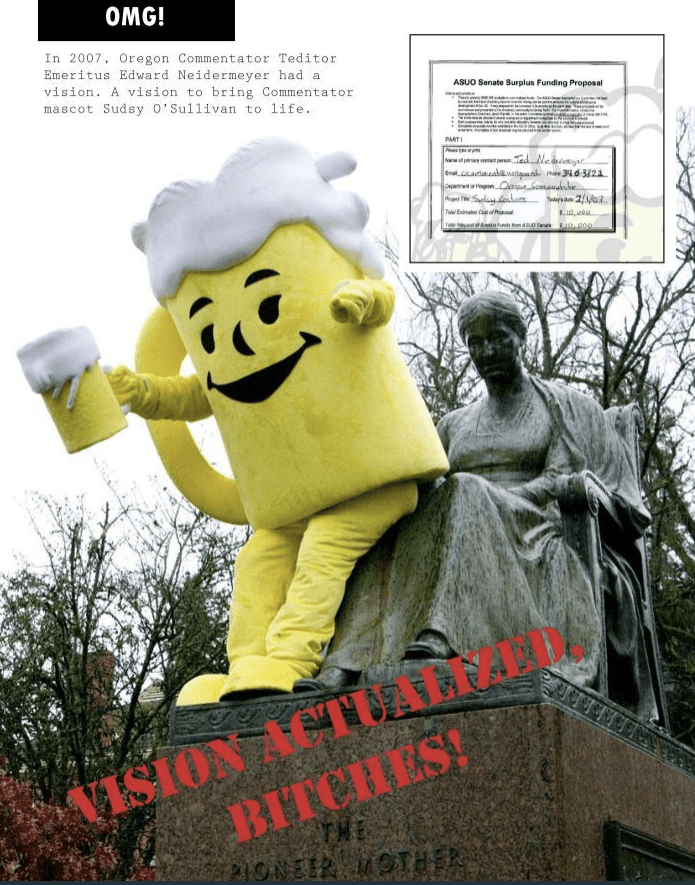

To commemorate this miracle of globalization, the editor at the time got a picture of it lap dancing the campus statue called “The Pioneer Mother” and created the following back cover.

Thus, Sudsy O’Sullivan entered the physical realm and for a few idyllic years he could be spotted around campus and at football games, bringing cheer to college kids who had no idea that they were getting excited about a “conservative” magazine’s mascot. But Sudsy’s transcendence from the pages of The Commentator also spelled the beginning of the end of that publication, which slowly lost its mojo until one day nobody showed up anymore and it was shuttered after more than 25 years. Sad as it was, at least Sudsy never had to suffer the indignity of being appropriated by Trumpism.

Sudsy’s mystical passage from the realm of ideas into reality is a fun college story to tell, but discovering in 2023 that you can (at least in theory) actually buy him online made me think about the experience in a different way. In particular, it touches on something I’ve been musing about lately, thanks to the work of Joseph Weizenbaum: the expectation of control in our computerized age. In discussing what he calls “compulsive programmers,” Weizenbaum notes how unique the absolute control that a computer enables really is:

“No playwright, no stage director, no emperor, however powerful, has ever exercised such absolute authority to arrange a stage or a field of battle and to command such unswervingly dutiful actors or troops.

One would have to be astonished if Lord Acton’s observation that power corrupts were not to apply in an environment in which omnipotence is so easily achievable.”

Nearly half a century later, computer-enabled control has seeped into every part of our lives and is dramatically changing how we see and value things. The constellation of apps on our phones help us control our lives in countless unprecedented ways, even allowing us to control how people perceive us through social media. Each of us wield powers that would be nothing short of fantastical at any other time in history, with the ultimate effect that we are more anxiety ridden than ever before. The more we control our exterior worlds, the more out of control our inner worlds feel.

The story of Sudsy’s transubstantiation (TransSudstantiation?) is a reminder that none of us is ever really in control, and that all meaningful cultural production is a chain of collaboration that connects humans to each other. My Oregon Commentator forefathers made Sudsy without having any idea what it would become, I made a joke to fill a page without having any idea what it would become, and the kid who talked his parents into making him a costume for a campus publication never aspired to any more than having fun at school. At each stage of this mystery, Sudsy’s servants needed to do nothing more than embrace the joy that is so evident in his trademark-violating eyes, and to do what they could to spread it a little further.

Leave a comment